from an Article in PilotOnline.com, 4/14/2014.

Granite monuments set more than 150 years ago mark a baseline surveyed on the Outer Banks. A ceremony on April 11, 2014, honored the work done by survey team leader Alexander D. Bache, a great-grandson of Benjamin Franklin. (Courtesy of the National Park Service)

The Virginian-Pilot

©

NAGS HEAD, N.C.

A nearly 7-mile string of granite monuments set on Bodie Island in 1848 – all still in place – mark one of the first official surveys of the Outer Banks.

The markers formed a baseline for mapping the coast and its waterways, from ocean to inland rivers.

“They knew they were setting the foundations for American geodesy,” said Bobby Stalls, a retired surveyor from the North Carolina Department of Transportation. Geodesy is the science of measuring the Earth.

Stalls spoke Friday to about 50 people gathered in a clearing around the northernmost monument deep in the brush near a National Park Service rest stop. Representatives from the National Geodetic Survey, the North Carolina Geodetic Survey and the North Carolina Society of Surveyors attended along with other guests, standing among pines and wax myrtles during the ceremony dedicating and celebrating the original work.

President Thomas Jefferson in 1807 set up the Survey of the Coast to establish safe passage into U.S. ports and along the coastline. First mapped were Maine, New York, Maryland, the Outer Banks, South Carolina, Florida and Alabama, along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico.

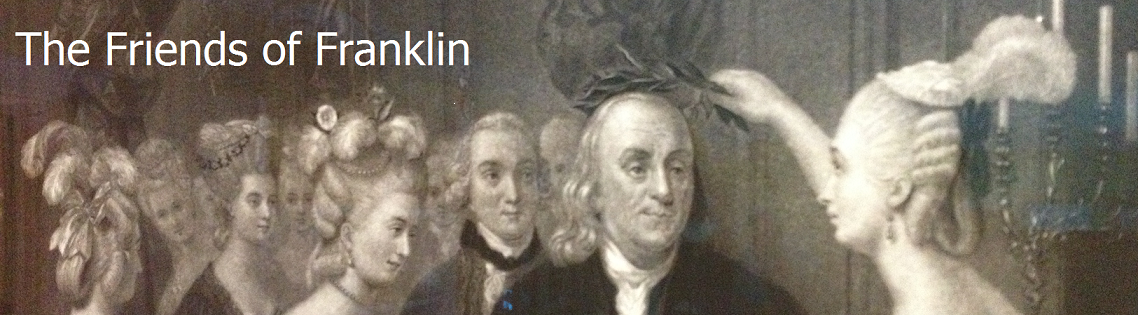

The Bodie Island markers are the only complete set remaining, Stalls said. Alexander D. Bache, a great grandson of Benjamin Franklin, led the project.

The original Survey of the Coast was the predecessor of the National Geodetic Survey, the agency responsible for mapping the nation. Brass and bronze markers placed all over the country serve as base points for surveyors locating bridges and buildings.

The 1846 storm that opened Oregon Inlet interrupted the Bodie Island survey, according to a history provided by the North Carolina Society of Surveyors. Eleven sailors – including Bache’s brother – were washed overboard and lost.

The inlet severed the original line. Bache considered building a bridge. Instead, he moved the baseline, running it 6.75 miles from the new shoreline north to the monument where Friday’s group gathered. He set granite markers about 1 mile apart.

“They wanted it to last,” Stalls said. “They needed it to last.”

A 2000 mapping project by the state Department of Transportation rediscovered the granite marker 36 inches square at the north end of the original baseline for the first time since the 1970s. Another monument sits close by, marked with Bache’s name. A team of volunteers cleared brush and found the other markers along the line two years later.

Park Service workers cleared a path of about a third of a mile from the rest stop to the monument. A modern survey of the baseline found the measurements were accurate within 5 inches, Stalls said.

“That’s amazing,” he said.

Jeff Hampton, 252-338-0159, [email protected]